CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE INTERVIEW

Summer 2007 - Volume 48 - Number 2 - The University of Wisconsin Press

an interview with Cristina García, conducted by Ylce Irizarry

Cristina García's debut novel, Dreaming in Cuban (1992), was not only pivotal in the career of its author but also a watershed moment for Latina/o literature. Nominated for the National Book Award, Dreaming in Cuban has been included on university and high school reading lists nationwide, and portions of it have been anthologized. Beyond simply propelling its author's renown, the book increased the visibility and acceptance of Latina/o writing within the mainstream American literary canon. The novel's treatment of Cuban exiles' acculturation to the United States is compelling and the focus of much of the scholarship on the book. Yet its exploration of Cuban citizens' acculturation to Castro's Cuba-presented through Cuba's intricate political and cultural history-is equally provocative. This acculturation is the basis for García's subsequent novels, The Agüero Sisters (1997) and Monkey Hunting (2003).

Cristina García was born in Havana in 1958. Her parents chose to live in exile when Castro assumed power. Because she was two years old when they left, she has no memories of Cuba; this lack has shaped her academic interests and pervades her writing, where memory is a constant motif. García grew up in New York City and attended Barnard College. After completing a master's degree in international relations at Johns Hopkins University, García began a decade-long period of work in journalism, ultimately attaining the position of bureau chief for Time magazine in Miami. Beginning in 1990, she devoted herself full-time to writing fiction. She has been a Guggenheim Fellow and a Hodder Fellow at Princeton University and received a Whiting Writers Award in 1996. She has been a visiting writer in residence at UCLA and at Mills College. Last summer, she was a workshop leader for the Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation Summer Writing Workshop for Writers of Color, VOICES.

The Agüero Sisters and Monkey Hunting depart significantly from Dreaming in Cuban in that they examine the cultural and political legacies of Cuba's colonial past rather than its more recent, communist history. Appearing within years of the one hundredth anniversary of the Spanish American War, these novels traverse time and place in a rich engagement of Cuba's histories--cultural, racial, and natural. Both novels continue the provocative experimentation with narrative voices and story lines that García began in Dreaming in Cuban. The Agüero Sisters, for example, features a first-person male narrative voice, in a shift from a matriarchal to a patriarchal point of view. The novel offers a nuanced treatment of the kaleidoscope of race, sexuality, and class in pre-Castro Cuba. Monkey Hunting presents another version of Cuban cultural history in its depiction of the experiences of Chinese immigrant laborers in nineteenth-century Cuba. The novel moves from China to Cuba to America and back to China in a narrative flow that is a hallmark of García's writing, as she intertwines the lives of her characters across geographies and between eras. While all three novels stand as individual narratives, they share common threads in García's history quest to uncover the essence of Cuba and its people.

In addition to her novels, García has published short stories and essays; edited anthologies of Cuban literature and Mexican and Mexican American literature; and written an introduction to a bilingual edition of the poems of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. Her fourth novel, A Handbook to Luck, was published in April 2007 and showcases García's belief that a writer should continually experiment and defy artificial reader expectations: it explores the lives of displaced characters not only from Cuba, but also from Iran and El Salvador.

This interview took place by telephone in February and July 2006. García had recently completed A Handbook to Luck and had begun work on a novel in a new voice, that of a young adult.

Q. Your writing has been instrumental to the way your readers perceive Cuba: your novels, in particular, have been opportunities for readers worldwide to conceive of Cuba as something other than a communist nation that the U.S. embargoes. The success of your first novel helped develop what we can now call a body of U.S. Latina/o literature, but perhaps more importantly, Dreaming in Cuban paved the way for the writing of your second and third novels, both of which explore Cuba's colonial and multicultural history. Your writing has several constant threads, among them history, violence, and memory. Let's begin with history. Perhaps the sentence most often quoted from Dreaming in Cuban is "And there's only my imagination where our history should be" [138]. The Agüero Sisters and Monkey Hunting were written and published at what some would call a critical historical moment, the end of a millennium. And 1998 was a critical year for Caribbean Latinos for a different reason: what role, if any, did the impending hundredth anniversary of the Spanish American War play in the writing of The Agüero Sisters?

A. I was not thinking specifically about the anniversary as an anniversary and something to focus on, but I did think an enormous amount about the fallout from the Spanish American War, how that affected Cuba's place in the world and its sense of itself. It played a part in the consciousness of my main character, Ignacio Agüero; he refers to that time period again and again. I was more interested in how the Spanish American War was a historical divide in terms of what happened physically to Cuba. Cuba went from having a rural economy to a largely urbanized economy. It became increasingly defoliated as more land was planted with sugarcane, tobacco, and so on. This period was one of enormous upheaval, and the changes came on the very edge of a big empire-the United States-that was increasingly throwing its weight around the world. For all of those reasons, that juncture was crucial for Cuba's history. To this day, things are playing out that were set in motion during the Spanish American War.

Q. I had supposed that the major changes in the economy, and certainly the natural history of Cuba, were on your mind as you were thinking about and writing the novel. Each of your novels seems to reach further back in Cuba's political history. Dreaming in Cuban is set in the years immediately before and one generation after the rise of communism in Cuba. The Agüero Sisters begins at a pivotal moment, the seeming exodus of the United States from Cuba in 1902, and ends in the 1980s. Monkey Hunting stretches furthest in time and space, beginning in China in the 1800s and then ending in the U.S., again in the 1980s. Could you describe the relationships among these novels, specifically how you chose which aspects of Cuba's political, natural, and cultural history to explore?

A. It is funny to think about those books in retrospect. Halfway through writing Monkey Hunting, I was thinking of them as making up a loose trilogy. I did not set out to do that, and it is odd to think of them that way now, because each one is its own entity with its own challenges, obsessions, and preoccupations. Really, it was only when I was halfway through Monkey Hunting that I realized that what I was trying to do, literarily, was to amplify an appreciation for the complex history that is Cuba. For me, growing up in an exile home with very anticommunist parents meant that I had a very limited notion of what Cuba and Cuban history meant. Everything revolved around the revolution; it was the big B.C. and A.D. of our lives. Yet there were all these stories-preceding and postdating and knocking things around so much-that I thought were equally important. I set out to explore Cuban history for myself in all its interesting permutations, in all its curious contributions from the far-flung corners of the world. I think that is what led me to write Monkey Hunting. Aside from Cubans and Cuban Americans, very few people knew that there were Chinese in Cuba. The Chinese presence predates by over a century this whole notion about multiply-hyphenated identities and multiracialism. The mixing was already present, but we didn't have the language to describe it. So I guess the novel was a chance to amplify my own sense of Cuban history.

Q. While reading each novel, I didn't think about them as a trilogy, either, but when I finished Monkey Hunting, I was struck by their convergences. Together, they do amplify that historical intricacy, yet they do some very interesting things as individual narratives as well. For example, The Agüero Sisters reveals a preoccupation with natural history. What is the relationship, for you, between the natural history of Cuba and its human history?

A. A large part of the deforestation and land cultivation began in the 1800s. It continued full force in the early 1900s, compromising Cuba's natural state even more. This process was absolutely related to Cuba's relationship with the United States. The more Cuba "developed," the more unnatural it became. The political and social alliance with the United States really meant the denaturalization of Cuba. I would say that they are parallel movements.

Q. You also explore this history through the confession-I like to call it a confession-of Ignacio Agüero, and you juxtapose it with the very unnatural expression of Cuban womanhood represented in Constancia's development of makeup products called Cuerpo de Cuba. Can you comment on this juxtaposition, as well as on your use of Thomas Barbour's A Naturalist in Cuba?

A. First, I do think the themes you mentioned-history and violence-play out in each of the novels. And about Barbour-I loved that book. I relied heavily on it to write Ignacio's sections in particular. I read many accounts by naturalists, from a variety of places, who went to Cuba in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to give me a sense of what Cuba used to be. I was struck by how each of them demonstrated the curiosity and scrutiny that Cuba has always been under, whether it is political or from the point of view of herpetologists or some other kind of scientist. Cuban culture is truly a crossroads; however, in terms of natural history, it is utterly unique. When I discovered how unusual and specific to Cuba a lot of its flora and fauna was, it was an irresistible way to approach history through fresh eyes and from a topographical point of view. That really, really appealed to me. I also like the other part of your question, about the unnatural versus the natural. I actually didn't think of the cosmetics as unnatural, but I think you are right; along with the skin grafts that Reina undergoes in Cuba, they reflect an intense attempt to create or manipulate perception about what is supposed to be natural. I think the concept of what is natural to Cuba or to a Cuban is definitely a working out of historical nostalgia-her Cuba, our Cuba. Everyone has his or her version of Cuba. Everybody-and I mean that collectively, including the exile community and Cubans in the diaspora-claims Cuba and makes its history his or her own, just as everyone does in families. Cuba is like Blanca Agüero: she is the recipient of all kinds of projections, and not just by Cubans. Everyone uses Cuba for his or her own purposes. This was another way for me to get away from writing about Cuba strictly in terms of the revolution.

Q. How does the struggle with what is supposed to be natural shape the actions or choices of your characters?

A. I think they are struggling on more fronts than a lot of people do, or in a heightened fashion. They struggle with dual identities and with two different political systems. Moreover, they struggle with the past and the present in an acute way within the Cuban context. As I am shepherding the characters, all of these things come into play, and I am juggling all of these preoccupations. Sometimes one takes over, and then another becomes more important, but then the first one resurfaces in a slightly different way. Character development is about balancing preoccupations; I develop the characters from my own imagination, but they have to have their own logic. No matter how extreme or crazy they seem, they have their own internal logic.

Q. That's very realistic. People have preoccupations that fluctuate in seriousness. There are things, like memory, that individuals push aside for some time and that come back to them, despite their efforts to forget.

A. Right. Some things are more pressing than others, and these things are conditioned by time. From the past, the characters inherit certain things; in the present, though, they create narratives for themselves or are swept up by circumstances and events. What strikes me more is the notion of Cuban identity-the rigidity involved in that. I am interested in how Cubans are constantly defining each other and what it means to be Cuban. This is something I played with a lot in The Agüero Sisters. Neither of the sisters fits into strict notions of cubanidad. Reina, for example, is not feminine in the ways she is supposed to be feminine, and Constancia is über feminine. Neither one fits into the Miami exile sense of cubanidad; they do not fit the political or cultural mores of the exile community. This whole natural/ unnatural thing works with the process of defining one's identity because that process is unnatural, too.

Q. It seems like there is a definition of the natural that you are working against. There are certain politics for Cubans-whether it is the politics of the Cubans on the island or the politics of exiled Cubans-which people want to seem natural or inevitably correct.

A. There is nothing natural about any of those politics; they are all constructs. So, yes, I'm interested in the wildernesses in between. For me, what is considered natural is usually really, really unnatural.

Q. In a similar way, Monkey Hunting explores cultural integration, which is often represented or perceived as unnatural. When I began reading Monkey Hunting, I felt a deep resonance with African American writing about the Middle Passage. Your descriptions of Chen Pan's travel to Cuba capture the tone and style of slave narratives, but what is also compelling is your development of a third kind of history, cultural, that emerges most intensely in this last novel. In the interview following the text of the novel, you state, "It's disturbing how the island's vibrant culture was forged under such brutality" (259-60). Tell me about your interest in specific aspects of Cuban culture in this novel, like Chinese apothecaries, African-influenced Santeria, and Cuban cuisine.

A. It is often said that the gateway to culture is food! I began there and was trying to work deeper down. My interest in cultural mixing began when as a child I loved that disparate foods could be brought together. The other part is my continued rebellion against the white-washed version of Cuban history that I grew up with. It still irks me when relatives say there were no racial problems in Cuba or that the Chinese only had laundromats in Cuba. They deny or dismiss the enormous cultural contributions of the many migrants to the islands. They don't see that without these contributions, we would not have the continually evolving, fascinating creature that is Cuban culture. Of course, my interest in hyphenated identities, particularly my own daughter's multiple identity, also plays a part in my trying to make what's different on the surface make a lot of sense.

Q. Another experience your writing tries to make sense of is violence against women. For example, Felicia suffers domestic violence in Dreaming in Cuban, Blanca suffers cultural displacement in The Agüero Sisters, and Chen Fang suffers political imprisonment and torture in Monkey Hunting. Do you see a particular relationship between violence against women and history?

A. Oh ... that is a huge question! The short answer is yes, absolutely. The long answer ... ah, where can I begin?

Q. Well, let's just take The Agüero Sisters and Ignacio's violence against Blanca. For me, this makes the novel as much a mystery as it is a cultural or political history. I am interested in the way his violence is a part of-not any greater or lesser than-his "natural history" of Cuba.

A. Strangely enough, I think Ignacio's violence is about idealism. It is the same impulse that Ignacio has in so-called preservation, in preserving dying or nearly extinct species. Of course, he is not helping the matter by shooting and preserving a few more species. I think that in him we sense a need to kill something, to murder something, to be able to hold it in your hands and gaze at it at your own leisure in order to be able to understand it. The book begins with Blanca's murder; by the end, it is almost a repeat of the beginning. It is sort of a long explanation, but not really an explanation of what happened, because there is no justification, no true rationalization for violence or, in his case, murdering his wife. Not for scientific reasons, not for personal reasons, not for reasons of jealousy, not for any of the myriad reasons that history gives for the subjugation of women. You can offer up many, many theories ... it is virtually inexplicable to me.

Q. I am curious about your comment that Ignacio's violence originates in some kind of idealism; if he holds a certain ideal about the preservation of nature or culture, why does he confess?

A. This sounds very harsh, but he killed things in order to understand them. He was not a bird watcher; he was an ornithologist. For at least two reasons, he needed to kill Blanca: she was an utter mystery to him, and he needed to put her under the glass; and she was something to collect and understand in his own fiction of Cuba.

Q. I can see why he tells the story; I can see why he tells the natural history. But he basically undoes his ideal Cuba in the confession.

A. Well, I think he was doing that all along. His collection of species contributed to the denaturalization of Cuba. He was decrying and contributing at the same time. As much as he decries the alliances to the U.S. and deforestation, the species he collects would have been better off reproducing or being left "undiscovered." As for his murder of his wife, there is something scientific about that, too. Blanca is-well, her name is the heart of the book----a blank narrative that he can write, which he must write. Of course there were emotions jealousy, anger, confusion-but really, his murder was scientific, and he couldn't exclude his science from his own fiction.

Q. One of the strengths of the novel is that it challenges readers to reflect on the causes of such violence, to think about human motivation and memory, which is a recurring thread in your writing. Memory sometimes takes on a life of its own, especially when characters like Reina say, "To be forgotten ... is the final death" 196]. At the level of narrative, how does your exploration of memory affect character development?

A. Essentially, memory is, over time, what you need your narrative to be. Why do we nurse this hurt over that one? Why do we remember one incident but not another? Memory is a reflection of our own fiction about our lives. Writing characters really means writing the fiction they would write about their own lives.

Q. What role does memory play in this novel or in your own thinking?

A. Memory is overrated. It is something that people think you can capture, but I think it is eternally elusive, subjective, and open to interpretation. That is part of its beauty, fascination, and frustration. This topic reminds me of how I and a friend from college are constantly battling, not just about interpretation, but about actual details of events we were at together. We disagree about little details about the costumes in a show or bigger things like what was going on in our lives at that time. I have come to understand memory as a personal necessity for creating one's own history. For me, it is not about reclaiming anything but about embroidering and discovering more about what I don't know about what I think I know.

Q. Some communications scholars argue that memory is culturally relative: people can recount the same events very differently yet with the same accuracy, since the kinds of details they relate are entirely different. That's certainly clear in the case of the Agüero sisters' memories of their mother's death. Their memories are shaped, if not created, by the narrative their father gives them, because he wants to create their memories of himself as well. He tries to do this with his "natural history" and his insertion of himself in its creation and documentation. Ignacio's narrative, you've already noted, was largely influenced by Barbour's text. Were you trying to create affinities between Ignacio's narrative and those of other naturalists writing about Cuba?

A. I think I was; I like to think of his narrative as an extension of that body of writing. People were drawn to the island because of its peculiarities, and I wanted his narrative to be part of that tradition. For the most part, foreigners wrote those narratives. I wanted Ignacio to assume that anthropological position; he takes the position of other outsiders.

Q. Ignacio tries to present himself as being from the outside, yet he is very invested in Cuba's culture and preservation. Earlier you talked about how the first naturalists reflected the way Cuba has been so scrutinized and used. Since the U.S. government continues to expand its use of the center for detention at Guantanamo Bay, would you like to express any thoughts about how Cuba is being used within the "war on terror"?

A. Well, frankly, I'm disgusted by the existence of the base. That is not to say that I am a big fan of the government of Cuba. I do believe in the sovereignty of nations, and it is a disgrace the way the Bush administration is just dismissing inalienable rights, basic legal rights, under the banner of a war on terrorism. It is truly horrible. Guantanamo exists-like other situations in Cuba-because of the Spanish American War. Yet I feel such sympathy and dismay for Cuba. I haven't been there in years, but I have friends who go more often. They say the whole country is depressed; there is such repression of minor businesses and small restaurants, etcetera. Worse, the repression of dissidence has increased, again.

Q. It seems that the repression occurs in waves; after the Pope's visit, there seemed to be more cultural openness. That may have been reversed after the Elian Gonzalez debacle. The movement between openness and repression may occur in other countries where dissidence is repressed, but as you say, we in the U.S. do seem to scrutinize Cuba, and I think in a way that denies its sovereignty. It will be interesting to see what happens if Castro's health continues to decline and Cuba is ruled by his brother or someone else.

A. Cuba has become more and more conservative and dogmatic, and it is a really grim place to be. Only my grandmother and my aunt remain there; through the 1980s and 1990s, everyone else in my family left. It is so sad that Castro has this stranglehold on the nation, as if no one else could do his job. It's the height of megalomania!

Q. Coming back to history in your writing, I want to ask if you see The Agüero Sisters and Monkey Hunting as fitting within a Latin American--or other---historical novel tradition.

A. Hmmm. I guess so, but when I am writing, I do not think of it as such. If I were to stand away from the novels, I would say yes. There is a historical novel tradition, and in the growing body of Latina/o literature, it is becoming a more common technique. I have noticed that historical subjects are more often explored within fiction, like Mario Vargas Llosa’s Feast of the Goat, or in the Latina/o tradition, Julia Alvarez's In the Time of the Butterflies. In my case, though, I am using historical events as a backdrop. I am not reimagining specific historical figures; my characters are spliced into larger historical events. I think this kind of writing is essential; there are so many novels today that have no context, are completely self-referential, entirely interior, or set on college campuses. For me, these novels have severely limited appeal. What I am attracted to, in terms of my own reading, and drawn to, in terms of my own writing, are stories that are part of a larger historical sweep. I'm hooked by stories that reverberate both ways, from the individual fictional characters out into the history and from the history back to and affecting, dislocating, and variously traumatizing or enhancing the lives of my characters. I think my writing may be a variation on the tradition, but I guess I never think of where my writing fits in with traditions or other writing while I am actually doing the writing,

Q. Is your forthcoming novel also set in a broad historical period?

A. It will be out in April-the galleys are done. I am very excited! Actually, the span of this book is the late 1960s to the 1980s; it is approximate to the present tense of Dreaming in Cuban. The novel is three disparate stories that somehow get intertwined. The characters from these stories are from places of revolution and upheaval: one character is a woman from Iran; another is a woman from El Salvador, who escapes the civil war there; and the third main character is a boy who leaves Cuba and ends up in Las Vegas, of all places. The characters are all children as the novel starts out; as it ends, they are in their twenties. The boy's father is a magician, so he grows up in late 1960s Las Vegas, and that has all sorts of complications. The characters variously meet, but not as extensively as I thought when I started. I guess the book is a very loose braid of stories. The book is about dislocation, loss, and luck.

Q. What is the renewed appeal of the contemporary period for you?

A. I think I am more preoccupied by contemporary migrations and dislocations. I wanted to see what other places have suffered dislocation. "Similar" is too strong a word, and "parallel" is not right either, but I wanted to explore places that experience political, not just economic, migrations. I have been living in L.A., where the Iranian presence is very strong, and while I was writing The Agüero Sisters, I had an office right in an Iranian neighborhood, so I became interested in the development of that presence. I also became interested in the experience of El Salvador and the dislocations of its people, because there are so many refugees from there. In the novel, the people come from very different cultural locations, but their lives become intertwined in L.A. Right now, I am interested in going beyond the Cuban model, beyond the loose trilogy I think the first three books work as. It is actually hard to imagine focusing only on Cuba anymore.

Q. Given all of the displacements that are occurring, do you think it's inevitable that refugees' lives intertwine in this way?

A. I think it depends on who they are and how much they want to live in a new identity. A lot of it is circumstance; things happen unpredictably. The book is called A Handbook to Luck because it questions notions of destiny and what is meant to happen or not. Of all my books, I think it is the most ambiguous.

Q. You started a move to the looser braid of stories in Monkey Hunting, with its development of interconnected but incomplete narratives. Where is the line between a novel and a loose braid of stories for you?

A. A Handbook to Luck is a novel; the stories do connect, the preoccupations and themes resurface for the characters even though they have radically different circumstances. I was trying to play with form a little, too. I get restless with one point of view and forward-moving plots. I am always interested in crosscutting and moving forward through the past, like I did in Monkey Hunting.

Q. I would say in Dreaming in Cuban, too. The first thing that struck me about that novel was the shifting between first-person and third-person narrative voices.

A. Strangely enough, I am trying an omniscient narration in another new book. I have never done that before-I am always cutting in with the first person. With this novel, I want to reread Anna Karenina and the nineteenth-century Russian novelists, because I think it needs to be omniscient; it takes place in seven days and is a sort of creation story. It is very hard for me to assume the omniscient view. I am having a hard time because I ultimately mistrust authorial omniscience-the official version of things, what purports to be all-knowing.

Q. Do you have a title for this book-in-progress?

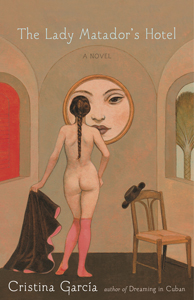

A. A working one: "The Lady Matador's Hotel."

Q. I like that. You have wonderful titles and phrases in your writing, like "the oppression of possibility," which appears in The Agüero Sisters, when Constancia is visiting her dying ex-husband in the hospital [139]. This phrase has such a wide range of applicability, and it has catalyzed my thinking about the book's depiction of empire and how nations are lost through political machinations. How do the themes and preoccupations you are interested in get translated into metaphors, images, or figurative language?

A. I think it is a combination of things ... sometimes you get that gift. Most of the time, though, I am massaging, revising, and listening until it sounds right. It is always a pleasure to tinker with a sentence; it is what I love to do most.

Q. Whom do you like to read for language?

A. I like to reread Virginia Woolf for that stream of language and consciousness. Mrs. Dalloway is one of my favorite books. I like Chekhov for humanity and intuition and the small touches that reveal volumes. I turn to poets as well. I read a lot of the Spanish poets for rhythm and imagery and heartbreak, really.

Q. In your last two novels, your publisher has included interviews with you and study guides. What was the process behind that, and how do you think it affects reception of your work?

A. That was definitely a publisher's decision! They are doing that with more and more books, especially with ones they think could lend themselves to book clubs. It is a huge phenomenon, this book club thing. Including the interview and study guide is a marketing tool aimed expressly at book clubs.

Q. I thought that the guides were geared to schools, simply because they are called "study guides." I did enjoy the interview, though; obviously it gives the reader a chance to hear the author's voice. Did the interviews affect your writing or the way you think about your writing?

A. As for the interviews, they let me choose whomever I wanted to interview with. Scott Brown is my ex-husband; he is very smart, and he asked really good questions. It was very informal. The interview forced me to distill and say-as economically as possible-what I thought about the novels. That was very challenging.

Q. Last spring you were a visiting associate professor at UCLA. How does teaching impact or influence your own writing?

A. I was also a visiting writer at Mills College, so I was very busy, teaching-wise. I flew up to Oakland once a week; I normally do not teach that much. I don't think I am alone in saying that teaching mostly brings my writing to a standstill. I was fortunate that I was done writing the novel, so I was just editing it. In any teaching week, I am reading about two hundred manuscript pages of student writing. And it is not casual reading; it is close reading, thinking hard, and line editing, I do love it-I love the present tense of it and working with younger writers. In my own writing, I finish a book and then bury it, make it feel like the past, and try not to revisit it. Technically, I am supposed to be teaching workshops, but I end up teaching courses that are hybrids of literature and writing. We are constantly reading. We start every class by discussing a short story. One week it is an Alice Munro story and the week after, Borges. We workshop the stories, not from a literary criticism point of view but from a craft point of view. It raises the level of discourse for our own stories when we discuss them the same way; this learning process seems to be very effective.

Q. How do you teach students to craft a good story or to develop the voice of a character?

A. I usually shock all of the students the first day by making them read poetry. Nobody expects that, but I make the case for reading poetry daily. It is not just about the esoteric value of poetry but about a way of mining the unconscious for things the students don't even know that they know. More than anything, at the beginning, I am trying to encourage them to invite mystery into the work-things they only dimly perceive. I do not want them to focus on plot but to go where their obsessions and pleasure lead them and to trust those things--obsession and pleasure. There will be plenty of time later to make something of it. That is what I want them to get at-what's essential to them. I want them reading passionately and thinking of writing as discovery rather than as relating what they know. At Mills, I was teaching a novel course, and everyone was working on a first novel. They brought in fifty-page chunks of novels each week.

Q. I am curious about another side of writing and teaching the carryover of market taste into the classroom. In a 1993 interview in the anthology Puentes a Cuba, you said that it was only a matter of time until Latina/o writing was considered part of the mainstream [109]. But that was over a decade ago; do you think Latinalo writing has entered the mainstream?

A. Well, I think the literature is part of the mainstream to a much greater degree than it was back then. I think some kind of funny inversion has happened, where the so-called exotic or from-the margins literature-whatever misnomer you want to use-is now part of the American literary appetite. Something a bit insidious is happening, too. We were talking about this in my novel course. The students felt-and I agree-that in some novels, there is almost a sense of cynical pandering to audience. Especially with first novels, there is a sense of having to explain, translate, or emphasize the more colorful or folkloric aspects of one's culture to make it palatable to a mainstream audience. Writers internalize this; in workshops it is encouraged-"tell us more about the food, the pomegranates, etcetera"-and I think there is a danger to this zoological approach. You have to strike a balance that incorporates culture but not in this weird, anthropological way.

Q. How do you attempt to strike a balance, especially when working with editors and publishers?

A. I have been lucky in that my editor is from the subcontinent, from India. It has never been an issue because he completely gets it. He also runs the show, because he is editor-in-chief. This is atypical of publishing; he is a person of color, and he is my editor. I hear about this from other people, for example, from my friend Chris Abani, who is Nigerian. He had quite a bit of success with his first novel, which is set in Nigeria and does have a certain amount of that exoticism to it. His subsequent work, though, which is set in L.A., has met with tremendous resistance in the publishing houses. They want him to do a sequel to Graceland. There is a sense that when you've written something that evokes a response, houses want you to repeat it. It is something like the desire to make movie sequels. The marketplace is a reality. I haven't heard it from my own editor, but if you do a different book each time, you may lose readers. But I can't compromise my work; I write what I want. It is the kiss of death to try to predict what audiences want.

Q. I think for writers of color who happen to write about cultural issues, this remains a problem.

A. I think it does too. When all is said and done, publishing houses are businesses. With consolidations and the Barnes and Nobles of the world dictating what to read for the fall season, it takes a lot for a book to distinguish itself. And after the first novel, you drop off the face of the earth! Writers mature and go more deeply into their worlds, but few people go on to read the second and third or later novels because they are so invested in discovering "the great new novel of exotic ethnic lived experience." Yes, I think Latina/o writing is a bigger part of the mainstream, but we have to be careful to represent our writing and our culture on our own terms and not to be translating it or overexplaining it to imaginary audiences.

Q. Who are some authors who avoid this overtranslation while amplifying a reader's understanding of a certain culture or time in history?

A. In my graduate course right now, we have been reading W. G. Sebald's The Emigrants. I also enjoy working with Chris Abani's Graceland and Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red, which is really a novel in poetic form. For my undergraduates, I'm all across the map. I always start from Chekhov, though, and I have them read everything, for their own stories. I believe that writers need to read from many different sources. You never know where you'll get something that will help you figure out what you're trying to accomplish in your own writing.

Q. In addition to your novel writing, you have edited an anthology of contemporary Cuban literature, ¡Cubanísimo! How did you come to do that?

A. ¡Cubanísimo! was not actually my idea. An editor at Vintage-Anchor books approached me. At that time, there was no organizing principle, no idea of how to select the works, really. I was intrigued by the idea of the anthology itself, and so I started rereading lots of things and discovering voices. What kept coming up for me was music; I thought organizing the anthology around sound was a way to pay tribute to another aspect of Cuban culture, a way to dovetail the literature without overpoliticizing it. I have another anthology just out, called Bordering Fires, with writing from both sides of the border, Mexican and Chicana/o, and it is in English and Spanish. The same editor came back to me with this project. I was less hesitant, having worked on the first one, but I was also aware that I had not read as extensively in Mexican American writing. I thought, I am always telling my students not to be contained by artificial writing borders, so I decided to do it. I liked the idea of voices from both sides of the border under one roof, the two traditions speaking to each other, which is fairly rare, I think.

Q. You are crossing a writing border of your own by working on a book for adolescents. What interests you about that voice?

A. I'm very happy with this project; I've been percolating along fast and easy with it. I think a couple of things led me to it, really. My daughter has always been a huge reader, and recently, she has become less so. Of course, there are lots of things competing for the interest and time of a thirteen-year-old-TV, music, friends. I think, though, that good authors are not taking this age group as seriously as they do others. I can think of only a few books that are really good for her age group. The book was also prompted by the death of her grandfather, with whom she was very close. So the voices in the book alternate between a teenager and a Jewish grandfather. The voice reflects the concerns, interests, and goals of someone like my daughter, someone of multiply mixed heritages. This novel covers things that Harry Potter just doesn't cover.

Q. Do you see yourself exploring other genres of writing, like drama, nonfiction, or poetry?

A. Right now, I want to start another novel. I am interested in the whole empty nest idea. It seems like there are nonfiction books for couples about how to deal with this stage of life, but there's really nothing in fiction, especially for single mothers, about how difficult the loss is. Down the road, I am also interested in theater, for sure. For now, though, I think I will enjoy walking in the light of having finished a novel. Coming out of writing a novel is somehow liberating. It feels like years before I really come out of it, even after I've written the novel and seen it in print.

Q. You wrote journalism for a decade, so I am wondering if and how that writing shapes your fiction. Was journalism also a kind of writing that you didn't come out of for a while?

A. No, not at all. Journalism is quite different, I think. I became very comfortable with embracing new material in short periods of time: at the beginning of a week, I would know nothing about a topic, but by the end of the week I would be something of an expert. What you do to get there-tackling new material, researching, and getting to know the right people-has been invaluable in my writing, in writing Monkey Hunting, for example. The research process is probably the last vestige of my journalism career at this point. The constant fact-checking has translated into a constant questioning of the authenticity of my characters and narrative. And journalism was definitely helpful for getting me in the habit of writing.

Q. Do you see journalism as a kind of non-narrative? Do journalism and fiction share any affinities?

A. I think they are both forms of translation, really. As a journalist, you are trying to organize what you understand to be the facts at that point in time. They might not turn out to be the facts, but at that time, they seemed to be. I think fiction is translating intuition, dreams, and interior lives. It is an exterior versus interior thing. In fiction, you have both, but you also try to translate those interior worlds, which are not usually the purview of journalism. It is not really why; it is more where and how. In a perfect world, a journalist is not the interpreter. This has changed, though, with Fox news! When I was a journalist, I tried to convey what I saw, what people told me; I tried to represent everyone's view, despite my own point of view on the subject.

Q. It seems that you are committed to exploring various topics and genres. What goals have you set for yourself as a writer?

A. I do know that I want to do at least one more novel-at least five novels altogether. I would love to do a play, too. I think I want to change more once my daughter goes to college. It has been a really busy and crazy time, but reading and writing, as always, are very steadying. Without them, I feel like flotsam ... I anchor myself with reading and writing time every day. We've just moved, and I'll be closer to a friend who offers poetry classes. So for the immediate future, I think I may just dive into poetry.